Deer

Deer Snapshot

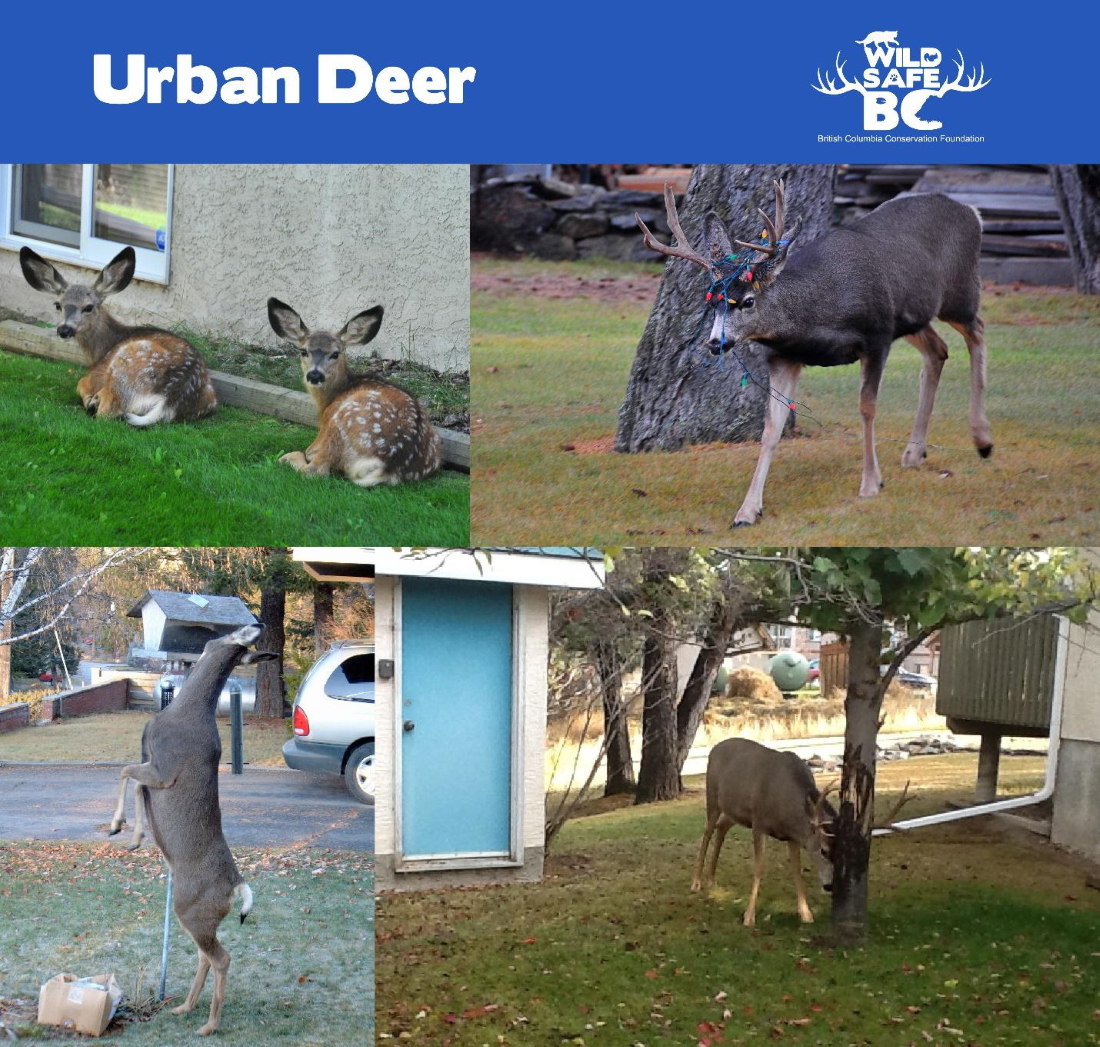

The Province of British Columbia is home to three types of deer: mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), black-tailed deer (also Odocoileus hemionus ) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). After black bears, deer are the most reported species to the Conservation Officer Service with an average of 4,500 reports per year. Urban deer conflicts are on the rise in many communities in British Columbia with increases in vehicle collisions and aggressive deer attacks on people and pets. Deer can also cause damage to gardens and crops resulting in significant losses. Deer are important prey for a variety of animals.

If you are experiencing conflict with deer, or believe you have found an abandoned fawn, call the Conservation Officer Service at 1-877-952-7277.

Wild Deer Facts

- Only male deer (bucks) have antlers. Antlers are shed annually in mid to late winter and are made of bone-like material

- Deer leave scent trails through pheromones in their interdigital glands (between toes); they also have metatarsal (outside of lower leg) and tarsal (inside of hock) scent glands

- Female deer (does) can be very protective of their young (fawns) and have been known to attack people and dogs

- Deer are prolific reproducers with 90 percent of does producing offspring every year once they are two years old; twins are common

- Fawns have no scent and will wait silently in a secluded place until the doe returns to nurse them. If you believe a fawn has been abandoned, do not approach it, leave the area and call the Conservation Officer Service. A doe may not return if they sense your presence

- Black-tailed deer are excellent swimmers and inhabit most of the coastal islands of BC

- Populations of mule deer in BC are between 20,000 to 25,000 in the north and approximately 165,000 deer in the Interior.

- Coastal black-tailed populations are estimated at 150,000 to 250,000

- White-tailed deer numbers are approximately 65,000

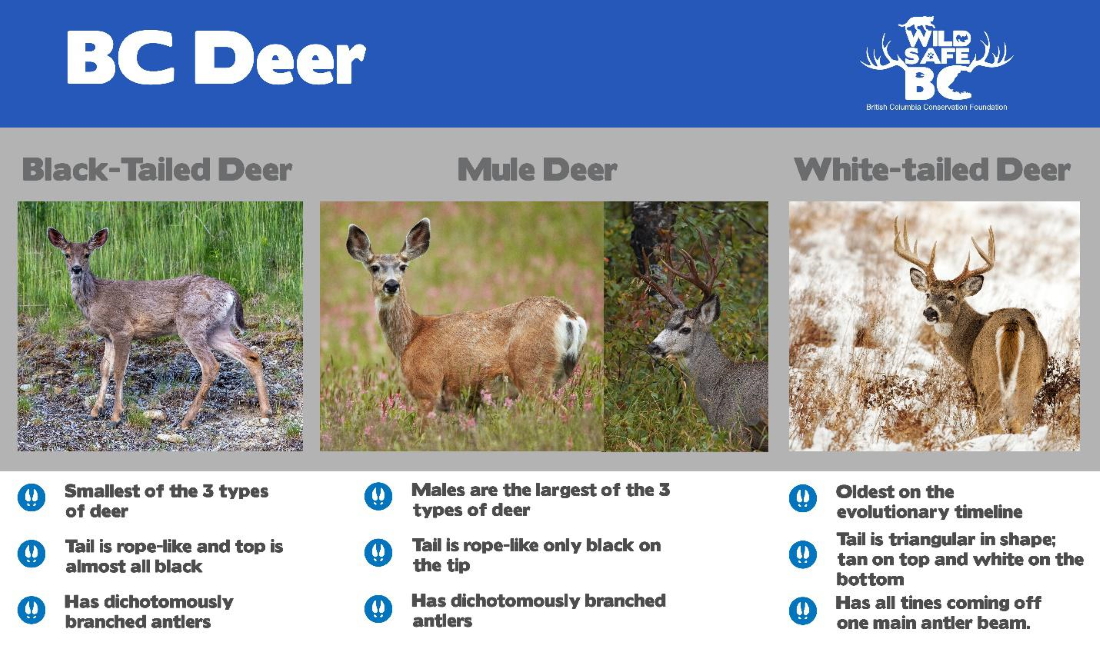

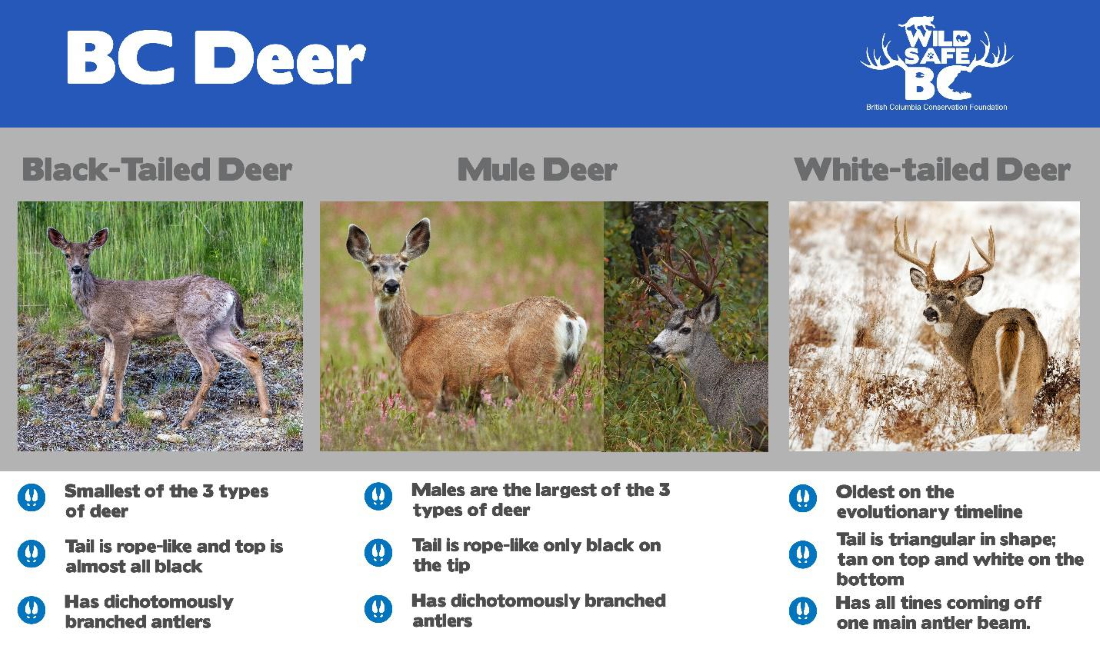

Identification

While all three types of deer in BC may seem similar, there are distinct physical and behavioural differences. White-tailed deer are the oldest species of deer in North America and the most widely distributed with many races/subspecies. Mule deer appeared most recently on the evolutionary timeline and are descendants of black-tail and white-tail interbreeding. Their evolutionary histories are complex and other subspecies/races in BC are: Rocky Mountain mule deer, Columbian black-tailed deer and Sitka black-tailed deer.

All deer are ungulates, or hooved mammals of the Order Artiodactyla, meaning even-toed ungulates. The key features for distinguishing the three types are their size, antler configuration and tail-colour. Mule deer and black-tailed deer have dichotomously branched antlers, meaning the antlers are forked and do not grow from a main beam. White-tailed deer antlers are not branched with all tines coming off a main beam. Only males have antlers which are made of bone and the number of points are not a good indicator of age. The antlers are shed mid to late winter with older bucks shedding first.

Biology

Males reach peak condition and size close to breeding season (the rut) in the fall which peaks in November. The mule deer rut occurs slightly ahead of the white-tailed deer. During this time the bucks will not eat and will lock antlers with other males to win the chance to mate with any receptive females in the vicinity. Females breed at an early age and may even do so in the same year as they are born. Fawns are born approximately 200 days later, usually in late May or June. Twins are typical but can also range from one to three offspring. Fawns are well-camouflaged from predators with spots and a lack of smell. Does will forage nearby while the fawns will wait silently for them to return and nurse them. By September, the fawns will have lost their spots and be weaned by October.

Males grow bony antlers every spring from a stubby protrusion called a pedicle. While they grow, the antlers are covered in velvet which provides the nourishment necessary for continued antler growth. Velvet is shed at the end of summer or early fall.

Deer can communicate using pheromones or scents produced by glands located between their toes (interdigital glands), outside of their lower legs (metatarsal) and inside their hock (tarsal). They use these scent glands to indicate alarm, identification and for leaving scent trails.

Deer are herbivores that are both browsers (eating parts of woody plants such as leaves, bark and stems) and grazers (eating vegetation from the ground such as grasses and non-woody plants) and have a four-chambered stomach making them ruminants. The process of ruminal fermentation allows deer to partially digest complex carbohydrates that other mammals cannot – this means that almost all vegetation is available to deer as a food source.

Cougars are the prime predators of deer. Bears, wolves, bobcats and coyotes tend to prey on fawns, elderly or injured deer. Deer typically live 8 to 10 years. Fawn mortality can range from 45 to 70 percent. Deer also die as a result of starvation, hunting and vehicle collisions.

Behaviour

Mule deer and white-tailed behave differently when threatened. Mule deer escape by stotting which involves bounding with stiff legs leaving the ground simultaneously. This allows them to clear obstacles and change directions quickly. White-tailed deer will gallop quickly away, often in a fairly straight line and will often raise their tail to display the snow white patch on the underside and wave the tail back and forth as if waving good-bye. This is termed flagging.

In BC, deer mainly travel alone or in small groups from May to October. In winter, large groups may gather around feeding areas. In late fall, deer enter into the rut (breeding season) which is triggered by the reduced photo-period of the short fall days. The rut generally peaks in mid-November and bucks will be in peak condition and exhibit swollen necks. Bucks will rub shrubs with their antlers, display dominance by strutting, circling and tail flicking. Mature bucks of similar size will engage in head-to-head fights and lock antlers. These displays and fights are used to assert dominance and secure breeding privileges. Bucks typically fast during the rut and this, combined with injuries sustained, may result in them being at increased risk of winter mortality.

Range and Habitat

Deer have winter and summer ranges and will migrate significant distances between the two. Deer will come down into valley bottoms in winter to avoid deep snow which makes travel difficult and increases their susceptibility to predation. Some deer may remain in valleys year-round but most will go up in elevation to feed on nutritious new growth. In temperate climates, ideal winter ranges will have mature trees capable of intercepting snow and providing forage such as twigs and lichen. In the Interior, mule deer will seek shrublands with shallow snow.

Black-tailed deer can be found along the coast of BC, Vancouver Island and most other coastal islands. Their densities are highest where winters are mild and snow is limited in depth. Mule deer populate the interior of the province. Where mule deer and black-tail ranges overlap, there can be hybrids with traits of both types. White-tailed deer are at the most northern part of their North American range and they are most abundant in the Okanagan and Kootenay regions. Their distribution is limited by climate and snow depths.

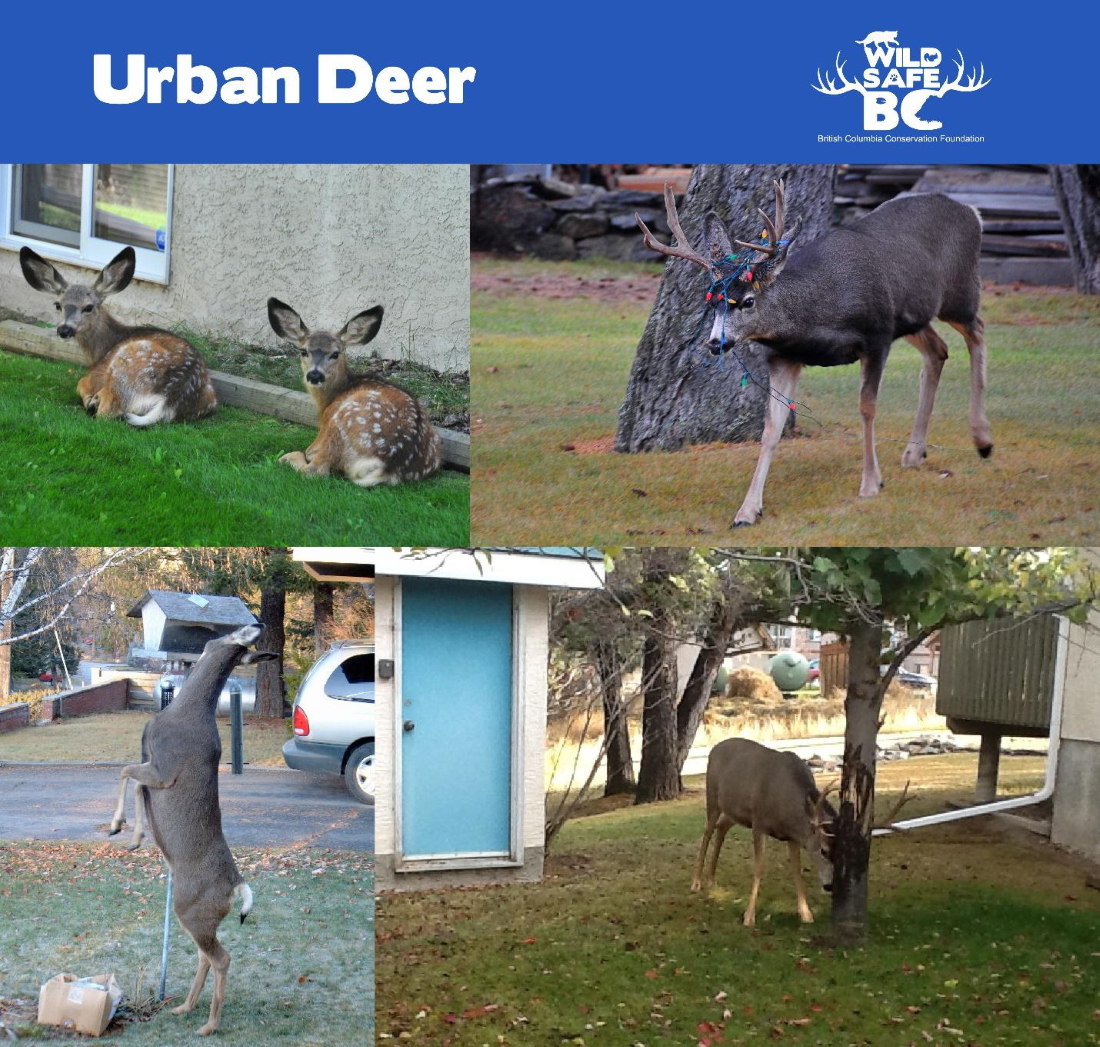

Highly adaptable, deer have learned how to survive and thrive in urban environments and cultivated landscapes.

Deer Safety

Deer conflicts are increasing in many communities as deer lose their natural fear of people and find food, shelter and safety from predators in urban communities. Deer are wild animals and you should never try to feed or approach them. Female does can be protective of their fawns and bucks may challenge you during the fall rut. Dogs can be perceived as a potential predator or threat. While attacks may be unpredictable, signs of an imminent charge include deer laying their ears back and lowering their head.

If you encounter deer, give them a wide berth and keep pets on leash and under control. If a deer indicates it may attack you or your pet, avoid eye contact, speak softly and back away slowly. If there is a tree or other solid object nearby, try to get behind it. If you have bear spray, it can also be used on deer if they get too close.

If you are attacked by a deer try to stay upright, cover your head with your arms and move to shelter. If you are concerned for your safety or have sighted deer in your neighborhood that are no longer afraid of people or pets, please report them to the Conservation Officer Service by calling 1-877-952-7277.

Every year, people die or are injured in vehicle-wildlife collisions. Use caution, especially at dawn, dusk and early evening when deer may be crossing roads. Become aware of where deer densities are highest and be extra vigilant in wildlife collision hotspots indicated by wildlife warning road signs. Learn more at wildlifecollisions.ca.

Deer, like all wildlife, have the potential to carry diseases or ticks that can impact other wildlife, livestock, people and pets. Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) first was reported in BC in 2024. The Province is actively monitoring for CWD and if you see ungulates (deer, elk, moose or caribou) that appear sick, please report them at 1-877-952-7277 or the BC Wildlife Health Program. Learn more about CWD here.

Conflict Reduction with Deer

Deer can be challenging and expensive to remove from a neighbourhood once they become established. Urban deer that have lost their natural wariness of people can become bold and potentially harm people and their pets. Their constant movement across roads can lead to increases in vehicle collisions. Deer can also cause damage to gardens, trees and agricultural crops. They not only browse crops but can damage trees by rubbing on them. Their presence can also draw in predators such as cougars. Below are some conflict reduction strategies.

- Do not feed deer intentionally. They are well-adapted to surviving on wild foods and feeding them rich foods in winter can actually lead to sickness and even death.

- Keep pets (dogs and cats) away from deer for their own safety.

- Leave fawns in place and do not approach them. If you believe a fawn has been abandoned, call the Conservation Officer Service. It is illegal to capture and transport deer without a permit. Does will often leave fawns to forage nearby. If you linger in the area, the doe may be hesitant to return to nurse.

- Deter deer from your property by chasing them away and using motion activated lights and/or sprinklers. Do not intentionally injure a deer in the process as it is illegal.

- Remove excess vegetative cover that deer may seek shelter in.

- Remove windfall fruit and keep fruit-bearing branches trimmed back and out of reach of deer.

- Ensure bird feeders are out of reach of deer and other non-target wildlife species.

- Deer-proof your yard as much as possible.

- Use wildlife-friendly fencing to exclude deer (see below).

Reducing deer conflict in your yard, garden, or farm

Deer can eat almost anything we plant but there are some plants that they find very appealing. For example, cedars are a common target by urban deer. A list of less-appealing plants can be found on the Master Gardeners of BC website.

Fencing can be effective at excluding deer. Refer to our NEW guide - Safer Fencing for Deer. Ensure your fencing is safe for deer and won't lead to serious injury or death through entanglement. Check with local bylaws before erecting a new fence.

Chain-link or woven-wire fencing should be at least 2.5 m high on level ground. The wires need to be taut to avoid entanglement. Avoid barb-wire fencing and decorative wrought-iron picket fences that can injure deer and are not effective at discouraging deer from entering your property. Solid board or panel fences can be lower (1.5 m high) and still be effective as deer are less likely to jump into an area they cannot see. Flexible mesh netting can also be used for individual plants but ensure deer cannot become entangled. Chicken wire can be used to wrap around trees and prevent deer from rubbing. In winter, shrubs and plants can be wrapped in burlap to prevent browsing.

For more advice and for large scale producers, refer to our Growing in Wildlife Country page.

Deer Resources

- BC Ecosystem Explorer

- Wildlife Collision Prevention Program

- Mule and Black-tailed Deer. Province of British Columbia

- White-tailed Deer. Province of British Columbia

- Deer-resistant plants. Master Gardeners of BC

- Living with Wildlife in BC: Ungulates. Advice for agriculture and rural land owners.

- Ticks in BC. Province of British Columbia

- Chronic Wasting Disease. Province of British Columbia

Deer Snapshot

The Province of British Columbia is home to three types of deer: mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus), black-tailed deer (also Odocoileus hemionus ) and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus). After black bears, deer are the most reported species to the Conservation Officer Service with an average of 4,500 reports per year. Urban deer conflicts are on the rise in many communities in British Columbia with increases in vehicle collisions and aggressive deer attacks on people and pets. Deer can also cause damage to gardens and crops resulting in significant losses. Deer are important prey for a variety of animals.

If you are experiencing conflict with deer, or believe you have found an abandoned fawn, call the Conservation Officer Service at 1-877-952-7277.

Wild Deer Facts

- Only male deer (bucks) have antlers. Antlers are shed annually in mid to late winter and are made of bone-like material

- Deer leave scent trails through pheromones in their interdigital glands (between toes); they also have metatarsal (outside of lower leg) and tarsal (inside of hock) scent glands

- Female deer (does) can be very protective of their young (fawns) and have been known to attack people and dogs

- Deer are prolific reproducers with 90 percent of does producing offspring every year once they are two years old; twins are common

- Fawns have no scent and will wait silently in a secluded place until the doe returns to nurse them. If you believe a fawn has been abandoned, do not approach it, leave the area and call the Conservation Officer Service. A doe may not return if they sense your presence

- Black-tailed deer are excellent swimmers and inhabit most of the coastal islands of BC

- Populations of mule deer in BC are between 20,000 to 25,000 in the north and approximately 165,000 deer in the Interior.

- Coastal black-tailed populations are estimated at 150,000 to 250,000

- White-tailed deer numbers are approximately 65,000

Identification

While all three types of deer in BC may seem similar, there are distinct physical and behavioural differences. White-tailed deer are the oldest species of deer in North America and the most widely distributed with many races/subspecies. Mule deer appeared most recently on the evolutionary timeline and are descendants of black-tail and white-tail interbreeding. Their evolutionary histories are complex and other subspecies/races in BC are: Rocky Mountain mule deer, Columbian black-tailed deer and Sitka black-tailed deer.

All deer are ungulates, or hooved mammals of the Order Artiodactyla, meaning even-toed ungulates. The key features for distinguishing the three types are their size, antler configuration and tail-colour. Mule deer and black-tailed deer have dichotomously branched antlers, meaning the antlers are forked and do not grow from a main beam. White-tailed deer antlers are not branched with all tines coming off a main beam. Only males have antlers which are made of bone and the number of points are not a good indicator of age. The antlers are shed mid to late winter with older bucks shedding first.

Biology

Males reach peak condition and size close to breeding season (the rut) in the fall which peaks in November. The mule deer rut occurs slightly ahead of the white-tailed deer. During this time the bucks will not eat and will lock antlers with other males to win the chance to mate with any receptive females in the vicinity. Females breed at an early age and may even do so in the same year as they are born. Fawns are born approximately 200 days later, usually in late May or June. Twins are typical but can also range from one to three offspring. Fawns are well-camouflaged from predators with spots and a lack of smell. Does will forage nearby while the fawns will wait silently for them to return and nurse them. By September, the fawns will have lost their spots and be weaned by October.

Males grow bony antlers every spring from a stubby protrusion called a pedicle. While they grow, the antlers are covered in velvet which provides the nourishment necessary for continued antler growth. Velvet is shed at the end of summer or early fall.

Deer can communicate using pheromones or scents produced by glands located between their toes (interdigital glands), outside of their lower legs (metatarsal) and inside their hock (tarsal). They use these scent glands to indicate alarm, identification and for leaving scent trails.

Deer are herbivores that are both browsers (eating parts of woody plants such as leaves, bark and stems) and grazers (eating vegetation from the ground such as grasses and non-woody plants) and have a four-chambered stomach making them ruminants. The process of ruminal fermentation allows deer to partially digest complex carbohydrates that other mammals cannot – this means that almost all vegetation is available to deer as a food source.

Cougars are the prime predators of deer. Bears, wolves, bobcats and coyotes tend to prey on fawns, elderly or injured deer. Deer typically live 8 to 10 years. Fawn mortality can range from 45 to 70 percent. Deer also die as a result of starvation, hunting and vehicle collisions.

Behaviour

Mule deer and white-tailed behave differently when threatened. Mule deer escape by stotting which involves bounding with stiff legs leaving the ground simultaneously. This allows them to clear obstacles and change directions quickly. White-tailed deer will gallop quickly away, often in a fairly straight line and will often raise their tail to display the snow white patch on the underside and wave the tail back and forth as if waving good-bye. This is termed flagging.

In BC, deer mainly travel alone or in small groups from May to October. In winter, large groups may gather around feeding areas. In late fall, deer enter into the rut (breeding season) which is triggered by the reduced photo-period of the short fall days. The rut generally peaks in mid-November and bucks will be in peak condition and exhibit swollen necks. Bucks will rub shrubs with their antlers, display dominance by strutting, circling and tail flicking. Mature bucks of similar size will engage in head-to-head fights and lock antlers. These displays and fights are used to assert dominance and secure breeding privileges. Bucks typically fast during the rut and this, combined with injuries sustained, may result in them being at increased risk of winter mortality.

Range and Habitat

Deer have winter and summer ranges and will migrate significant distances between the two. Deer will come down into valley bottoms in winter to avoid deep snow which makes travel difficult and increases their susceptibility to predation. Some deer may remain in valleys year-round but most will go up in elevation to feed on nutritious new growth. In temperate climates, ideal winter ranges will have mature trees capable of intercepting snow and providing forage such as twigs and lichen. In the Interior, mule deer will seek shrublands with shallow snow.

Black-tailed deer can be found along the coast of BC, Vancouver Island and most other coastal islands. Their densities are highest where winters are mild and snow is limited in depth. Mule deer populate the interior of the province. Where mule deer and black-tail ranges overlap, there can be hybrids with traits of both types. White-tailed deer are at the most northern part of their North American range and they are most abundant in the Okanagan and Kootenay regions. Their distribution is limited by climate and snow depths.

Highly adaptable, deer have learned how to survive and thrive in urban environments and cultivated landscapes.

Deer Safety

Deer conflicts are increasing in many communities as deer lose their natural fear of people and find food, shelter and safety from predators in urban communities. Deer are wild animals and you should never try to feed or approach them. Female does can be protective of their fawns and bucks may challenge you during the fall rut. Dogs can be perceived as a potential predator or threat. While attacks may be unpredictable, signs of an imminent charge include deer laying their ears back and lowering their head.

If you encounter deer, give them a wide berth and keep pets on leash and under control. If a deer indicates it may attack you or your pet, avoid eye contact, speak softly and back away slowly. If there is a tree or other solid object nearby, try to get behind it. If you have bear spray, it can also be used on deer if they get too close.

If you are attacked by a deer try to stay upright, cover your head with your arms and move to shelter. If you are concerned for your safety or have sighted deer in your neighborhood that are no longer afraid of people or pets, please report them to the Conservation Officer Service by calling 1-877-952-7277.

Every year, people die or are injured in vehicle-wildlife collisions. Use caution, especially at dawn, dusk and early evening when deer may be crossing roads. Become aware of where deer densities are highest and be extra vigilant in wildlife collision hotspots indicated by wildlife warning road signs. Learn more at wildlifecollisions.ca.

Deer, like all wildlife, have the potential to carry diseases or ticks that can impact other wildlife, livestock, people and pets. Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD) first was reported in BC in 2024. The Province is actively monitoring for CWD and if you see ungulates (deer, elk, moose or caribou) that appear sick, please report them at 1-877-952-7277 or the BC Wildlife Health Program. Learn more about CWD here.

Conflict Reduction with Deer

Deer can be challenging and expensive to remove from a neighbourhood once they become established. Urban deer that have lost their natural wariness of people can become bold and potentially harm people and their pets. Their constant movement across roads can lead to increases in vehicle collisions. Deer can also cause damage to gardens, trees and agricultural crops. They not only browse crops but can damage trees by rubbing on them. Their presence can also draw in predators such as cougars. Below are some conflict reduction strategies.

- Do not feed deer intentionally. They are well-adapted to surviving on wild foods and feeding them rich foods in winter can actually lead to sickness and even death.

- Keep pets (dogs and cats) away from deer for their own safety.

- Leave fawns in place and do not approach them. If you believe a fawn has been abandoned, call the Conservation Officer Service. It is illegal to capture and transport deer without a permit. Does will often leave fawns to forage nearby. If you linger in the area, the doe may be hesitant to return to nurse.

- Deter deer from your property by chasing them away and using motion activated lights and/or sprinklers. Do not intentionally injure a deer in the process as it is illegal.

- Remove excess vegetative cover that deer may seek shelter in.

- Remove windfall fruit and keep fruit-bearing branches trimmed back and out of reach of deer.

- Ensure bird feeders are out of reach of deer and other non-target wildlife species.

- Deer-proof your yard as much as possible.

- Use wildlife-friendly fencing to exclude deer (see below).

Reducing deer conflict in your yard, garden, or farm

Deer can eat almost anything we plant but there are some plants that they find very appealing. For example, cedars are a common target by urban deer. A list of less-appealing plants can be found on the Master Gardeners of BC website.

Fencing can be effective at excluding deer. Refer to our NEW guide - Safer Fencing for Deer. Ensure your fencing is safe for deer and won't lead to serious injury or death through entanglement. Check with local bylaws before erecting a new fence.

Chain-link or woven-wire fencing should be at least 2.5 m high on level ground. The wires need to be taut to avoid entanglement. Avoid barb-wire fencing and decorative wrought-iron picket fences that can injure deer and are not effective at discouraging deer from entering your property. Solid board or panel fences can be lower (1.5 m high) and still be effective as deer are less likely to jump into an area they cannot see. Flexible mesh netting can also be used for individual plants but ensure deer cannot become entangled. Chicken wire can be used to wrap around trees and prevent deer from rubbing. In winter, shrubs and plants can be wrapped in burlap to prevent browsing.

For more advice and for large scale producers, refer to our Growing in Wildlife Country page.

Deer Resources

- BC Ecosystem Explorer

- Wildlife Collision Prevention Program

- Mule and Black-tailed Deer. Province of British Columbia

- White-tailed Deer. Province of British Columbia

- Deer-resistant plants. Master Gardeners of BC

- Living with Wildlife in BC: Ungulates. Advice for agriculture and rural land owners.

- Ticks in BC. Province of British Columbia

- Chronic Wasting Disease. Province of British Columbia